…handle time series data?#

Import packages#

%matplotlib inline

import spyndex

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sdc.load import load_product

from sdc.utils import groupby_acq_slices

Loading data#

vec = '../../_assets/vec_01_05_01.geojson'

ds = load_product(product="s2_l2a", vec=vec)

ds = groupby_acq_slices(ds)

params = {'N': ds.B08, 'R': ds.B04, 'B': ds.B02, 'g': 2.5, 'C1': 6.0, 'C2': 7.5, 'L': 1.0}

evi = spyndex.computeIndex(index=['EVI'], params=params)

evi

<xarray.DataArray (time: 523, latitude: 131, longitude: 147)> Size: 40MB

dask.array<truediv, shape=(523, 131, 147), dtype=float32, chunksize=(523, 131, 147), chunktype=numpy.ndarray>

Coordinates:

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 4kB 2018-01-04T08:00:00 ... 2025-03-30...

* latitude (latitude) float64 1kB -25.06 -25.06 -25.06 ... -25.08 -25.08

* longitude (longitude) float64 1kB 31.47 31.47 31.47 ... 31.5 31.5 31.5

spatial_ref int32 4B 4326

Attributes:

nodata: 0Data exploration#

This example area is small and relatively homogeneous, so we can spatially average the EVI values to get a single time series:

evi_sm = evi.mean(dim=['longitude', 'latitude'])

evi_sm

<xarray.DataArray (time: 523)> Size: 2kB

dask.array<mean_agg-aggregate, shape=(523,), dtype=float32, chunksize=(523,), chunktype=numpy.ndarray>

Coordinates:

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 4kB 2018-01-04T08:00:00 ... 2025-03-30...

spatial_ref int32 4B 4326

Attributes:

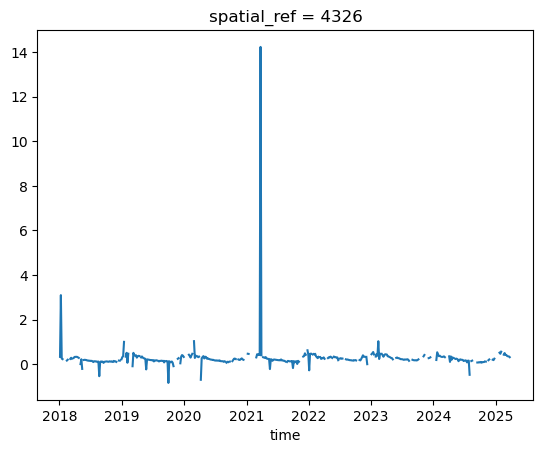

nodata: 0The .plot()-method automatically creates a line plot, which is not ideal when nodata values and outliers are present. Better to use a scatter plot:

evi_sm.plot()

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x7fd2f195e5d0>]

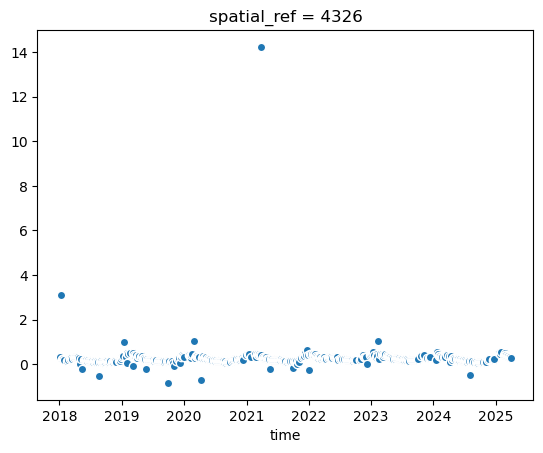

evi_sm.plot.scatter(x='time') # x-axis has to be specified!

<matplotlib.collections.PathCollection at 0x7fd2eaf0f740>

Let’s compute values so that we don’t have to re-compute everytime we want to access them (e.g. for plotting). We then convert the xarray DataArray to a pandas DataFrame for easier handling in the following steps:

vi_sm = evi_sm.compute()

evi_sm

evi_sm_df = evi_sm.to_series()

evi_sm_df

time

2018-01-04 08:00:00 0.331300

2018-01-09 08:00:00 3.099223

2018-01-14 08:00:00 0.252956

2018-01-19 08:00:00 0.228773

2018-01-24 08:00:00 NaN

...

2025-03-13 08:00:00 0.355623

2025-03-20 08:00:00 0.342944

2025-03-23 08:00:00 0.316812

2025-03-28 08:00:00 NaN

2025-03-30 08:00:00 0.263662

Length: 523, dtype: float32

# Easy to get some summary statistics with pandas

print("Total count:", len(evi_sm_df))

print("Nodata count:", evi_sm_df.isna().sum())

evi_sm_df.describe()

Total count: 523

Nodata count: 108

count 415.000000

mean 0.277122

std 0.720414

min -0.837399

25% 0.154266

50% 0.219401

75% 0.329128

max 14.230196

dtype: float64

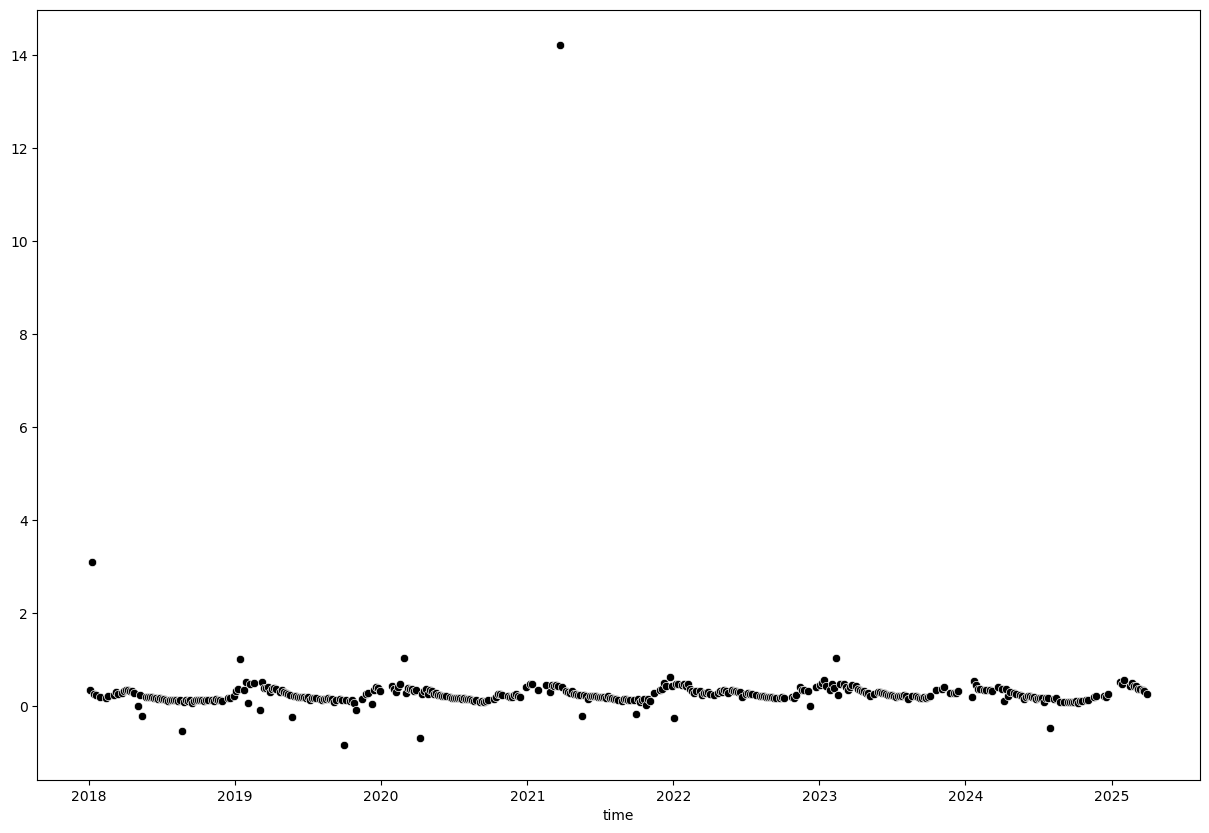

The library seaborn integrates well with matplotlib to create attractive statistical plots. We will use it from here on to create scatter plots of our time series data.

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df.index, y=evi_sm_df.values, color='black')

<Axes: xlabel='time'>

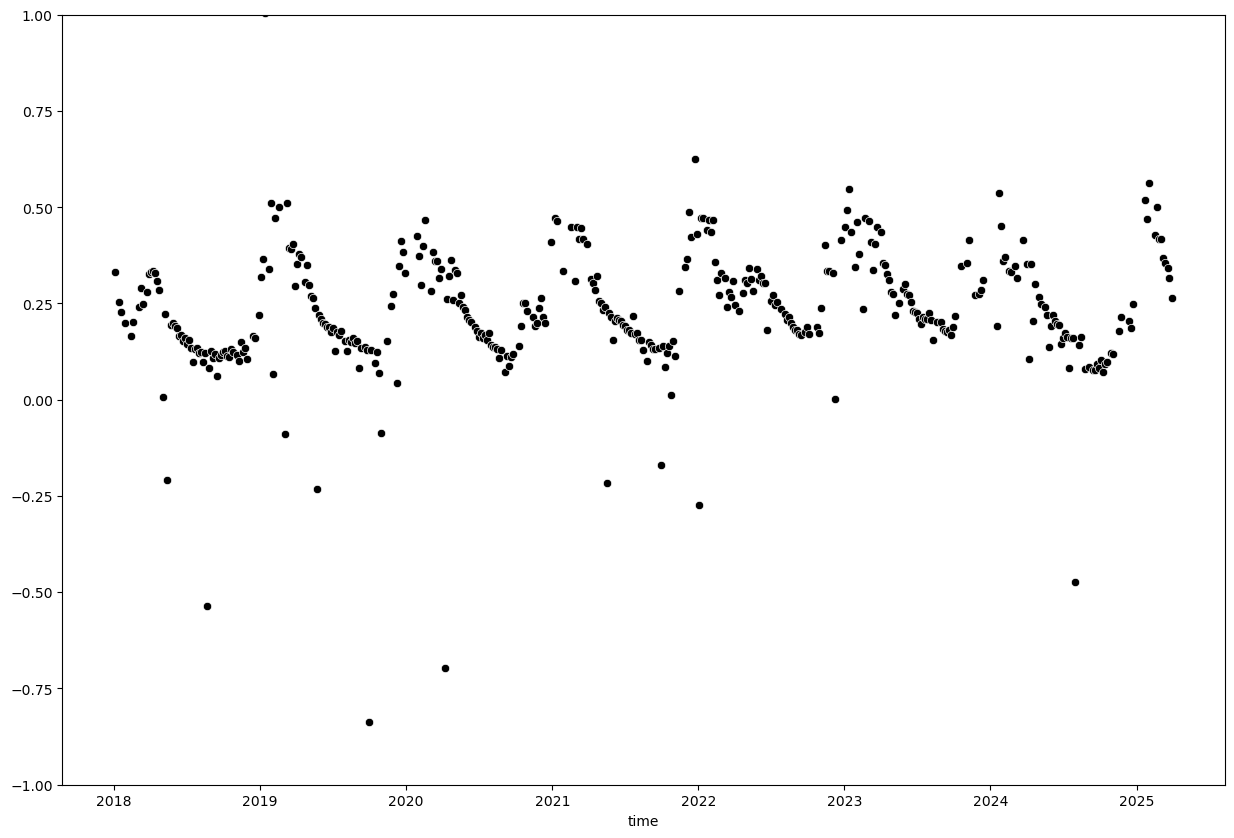

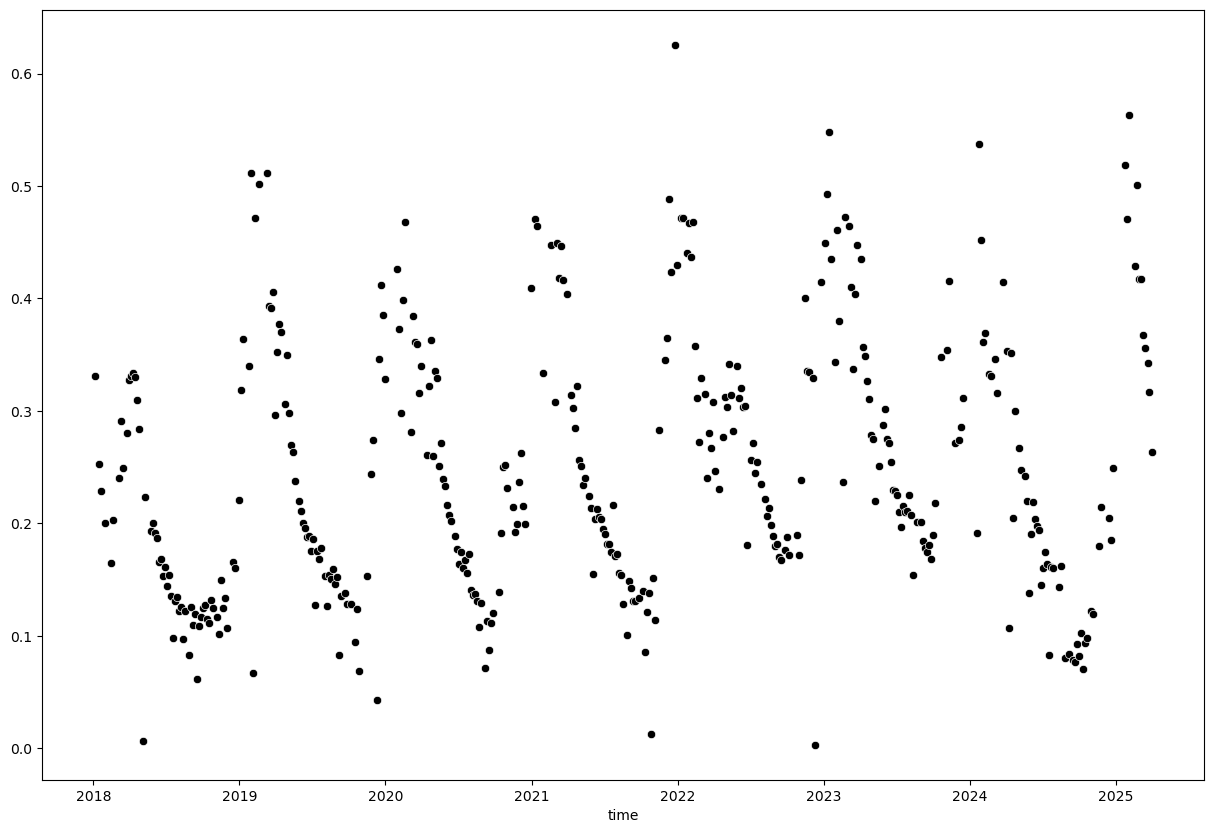

We can see a few extreme outliers. Let’s limit y-axis to valid EVI range to better visualize the data:

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df.index, y=evi_sm_df.values, color='black')

plt.ylim(-1, 1)

(-1.0, 1.0)

Outlier removal#

A simple threshold of 0 - 1 will not exclude all outliers but is a good starting point. Be careful with thresholding as you might exclude valid data points as well.

evi_sm_df_01 = evi_sm_df[(evi_sm_df >= 0) & (evi_sm_df <= 1)]

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01.index, y=evi_sm_df_01.values, color='black')

<Axes: xlabel='time'>

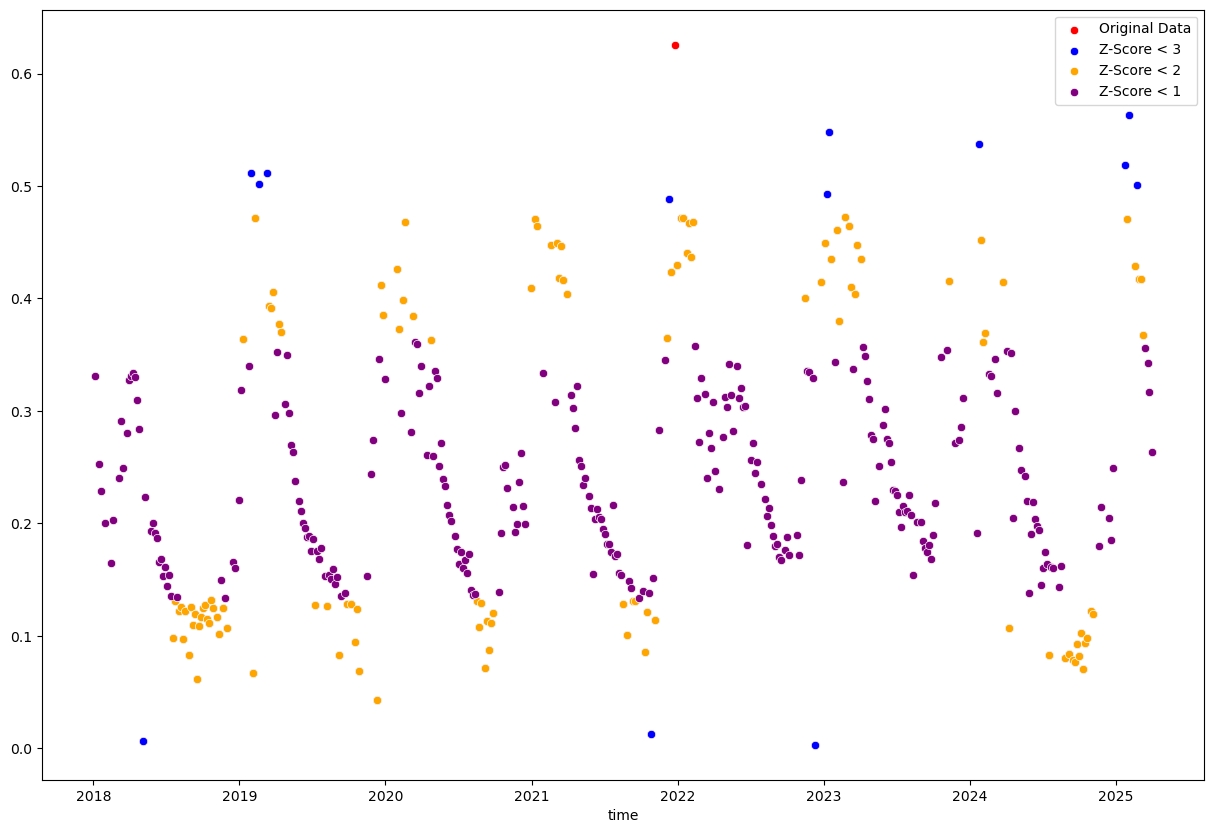

Instead of using a simple threshold, we can also use statistical methods to identify outliers. For example, we can use the z-score method to identify points that are a certain number of standard deviations away from the mean.

from scipy.stats import zscore

z_scores = np.abs(zscore(evi_sm_df_01.values, nan_policy='omit'))

z_score_flt3 = z_scores < 3 # Flag all values with z-score < 3 as True, others as False

z_score_flt2 = z_scores < 2

z_score_flt1 = z_scores < 1

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01.index, y=evi_sm_df_01.values, color='red', label='Original Data')

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01[z_score_flt3].index, y=evi_sm_df_01[z_score_flt3].values, color='blue', label='Z-Score < 3')

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01[z_score_flt2].index, y=evi_sm_df_01[z_score_flt2].values, color='orange', label='Z-Score < 2')

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01[z_score_flt1].index, y=evi_sm_df_01[z_score_flt1].values, color='purple', label='Z-Score < 1')

<Axes: xlabel='time'>

The single “Original Data” point is filtered out by all three z-score filters. The other colored points are the ones that remain after applying the respective z-score filters, with more points being filtered out as the threshold becomes stricter.

The stricter thresholds remove too many valid data points because it is applied to the entire dataset without considering temporal context. The z-score is calculated based on the mean and standard deviation of the entire dataset and assumes a normal distribution of values. In datasets with high variability or seasonal patterns, many valid points will be incorrectly flagged as outliers.

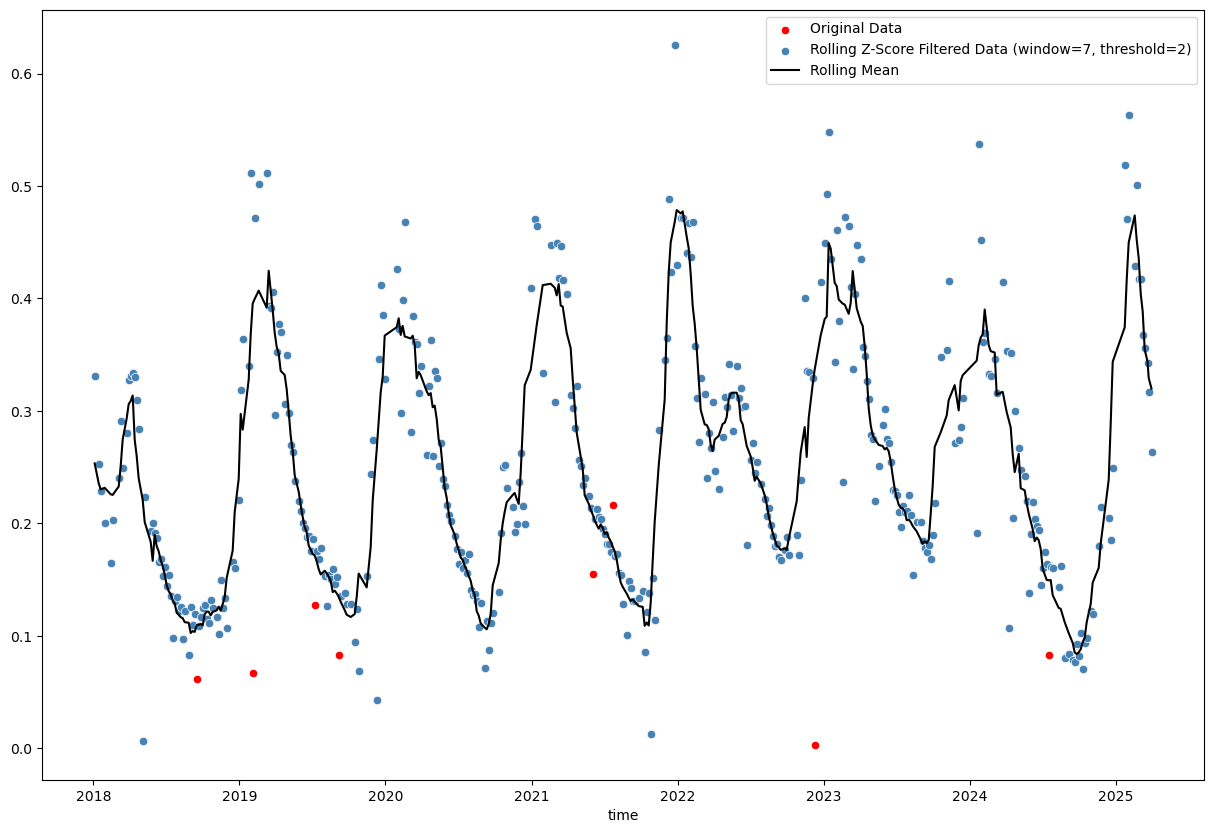

# Calculate rolling z-score

window_size = 7

rolling_mean = evi_sm_df_01.rolling(window=window_size, center=True, min_periods=(window_size//2)).mean() # use min_periods to avoid NaNs at start and end

rolling_std = evi_sm_df_01.rolling(window=window_size, center=True, min_periods=(window_size//2)).std()

z_score_rolling = (evi_sm_df_01 - rolling_mean) / rolling_std

# Identify outliers

threshold = 2

outliers_rolling = np.abs(z_score_rolling) < threshold

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01.index, y=evi_sm_df_01.values, color='red', label='Original Data')

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01[outliers_rolling].index, y=evi_sm_df_01[outliers_rolling].values, color='steelblue', label=f'Rolling Z-Score Filtered Data (window={window_size}, threshold={threshold})')

sns.lineplot(x=rolling_mean.index, y=rolling_mean.values, color='black', label='Rolling Mean')

<Axes: xlabel='time'>

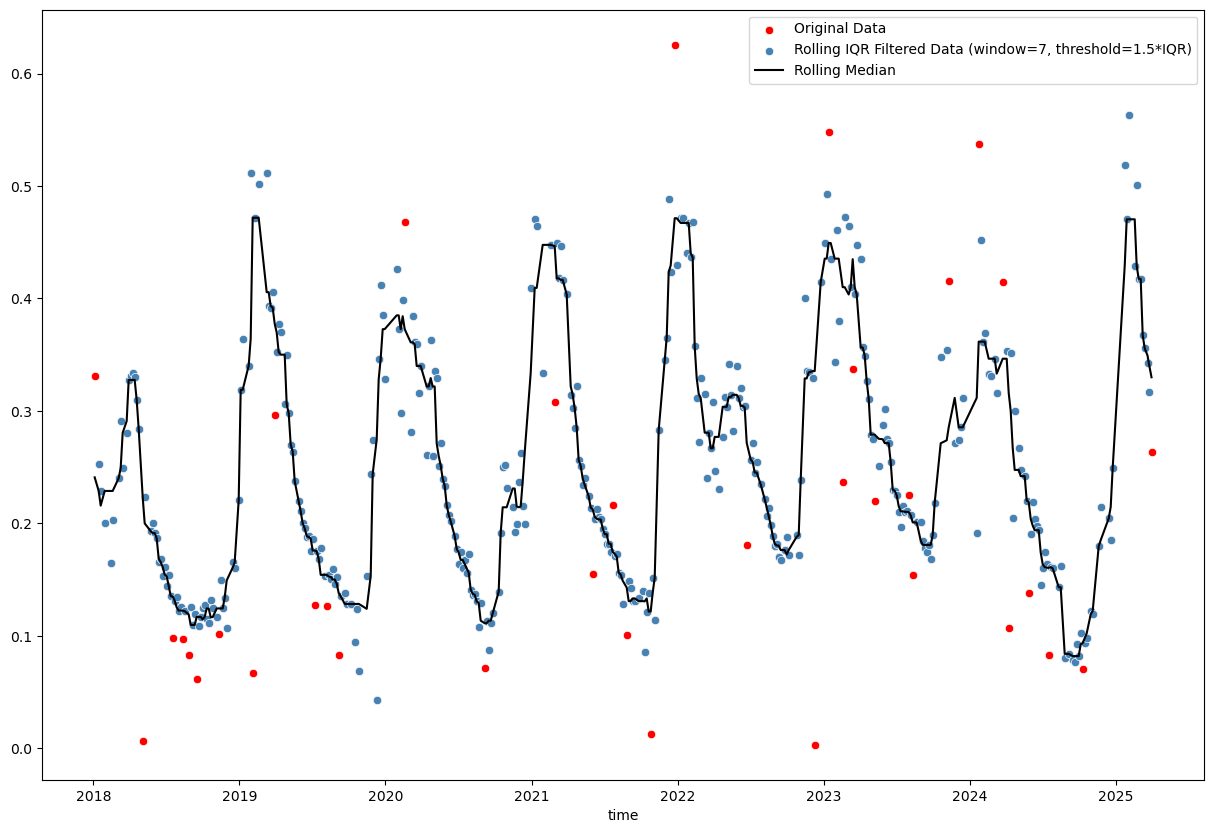

# Rolling IQR method

window_size = 7

rolling_median = evi_sm_df_01.rolling(window=window_size, center=True, min_periods=(window_size//2)).median()

rolling_q75 = evi_sm_df_01.rolling(window=window_size, center=True, min_periods=(window_size//2)).quantile(0.75)

rolling_q25 = evi_sm_df_01.rolling(window=window_size, center=True, min_periods=(window_size//2)).quantile(0.25)

rolling_iqr = rolling_q75 - rolling_q25

# Identify outliers (1.5 * IQR is standard, but can adjust)

threshold_iqr = 1.5

lower_bound = rolling_median - threshold_iqr * rolling_iqr

upper_bound = rolling_median + threshold_iqr * rolling_iqr

outliers_iqr = (evi_sm_df_01 >= lower_bound) & (evi_sm_df_01 <= upper_bound)

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01.index, y=evi_sm_df_01.values, color='red', label='Original Data')

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01[outliers_iqr].index, y=evi_sm_df_01[outliers_iqr].values, color='steelblue', label=f'Rolling IQR Filtered Data (window={window_size}, threshold={threshold_iqr}*IQR)')

sns.lineplot(x=rolling_median.index, y=rolling_median.values, color='black', label='Rolling Median')

<Axes: xlabel='time'>

Basic rolling z-score (using mean and standard deviation) and interquartile range (IQR; using median and quartiles) methods are tricky, because choosing the right window size and threshold is not straightforward. Furthermore, even a reasonable choice of these parameters may not yield satisfactory results, especially in the presence of seasonal patterns or trends in the data (as we can see in the plots above).

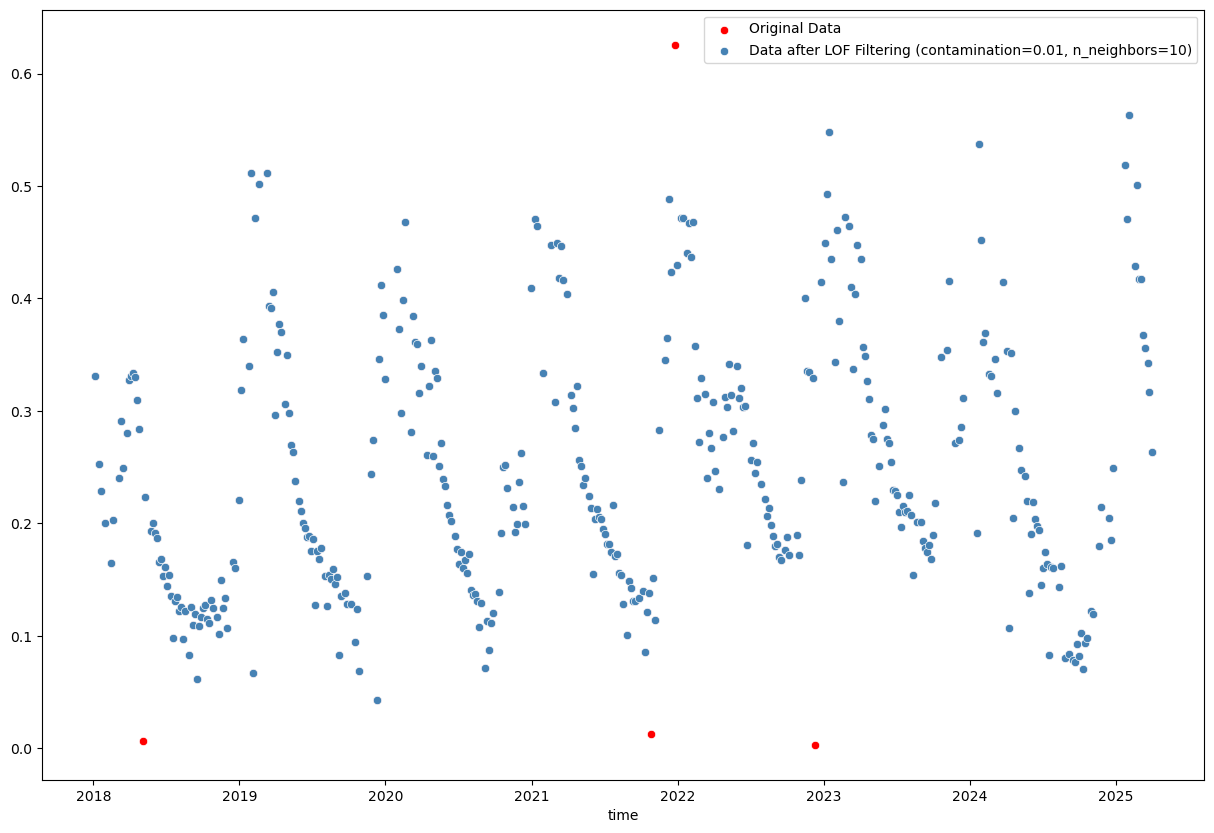

When googling “python outlier detection”, we end up on this page from the scikit-learn documentation, which introduces the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) and Isolation Forest methods for outlier detection. These methods are more sophisticated and can handle complex data patterns better than simple rolling statistics. Let’s try them out!

from sklearn.neighbors import LocalOutlierFactor

contamination = 0.01

n_neighbors = 10

# Experiment with these parameters to see how they affect the results. `contamination` defines the proportion of outliers in the data set and should be set according to your knowledge of the data (e.g., 0.01 for 1% outliers).

# `n_neighbors` defines the number of neighbors to use for the LOF algorithm and can affect sensitivity to local data structure (default is 20).

lof = LocalOutlierFactor(contamination=contamination, n_neighbors=n_neighbors)

lof_fit = lof.fit_predict(evi_sm_df_01.values.reshape(-1, 1))

lof_flt = lof_fit == 1 # In LOF, -1 indicates an outlier, 1 indicates an inlier

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01.index, y=evi_sm_df_01.values, color='red', label='Original Data')

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01[lof_flt].index, y=evi_sm_df_01[lof_flt].values, color='steelblue', label=f'Data after LOF Filtering (contamination={contamination}, n_neighbors={n_neighbors})')

<Axes: xlabel='time'>

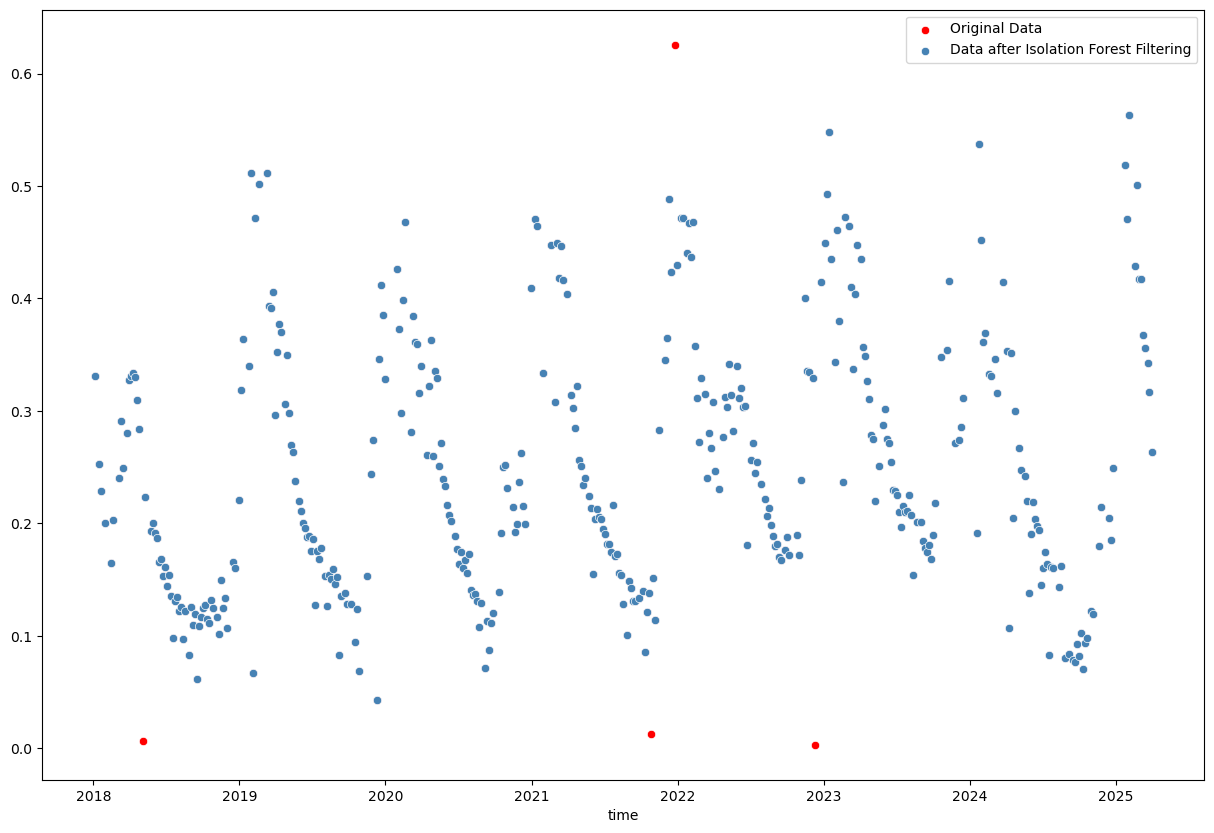

from sklearn.ensemble import IsolationForest

contamination = 0.01

# Similarly, you can experiment with the `contamination` parameter here.

iso_forest = IsolationForest(contamination=contamination)

iso_fit = iso_forest.fit_predict(evi_sm_df_01.values.reshape(-1, 1))

iso_flt = iso_fit == 1 # In Isolation Forest, -1 indicates an outlier, 1 indicates an inlier

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01.index, y=evi_sm_df_01.values, color='red', label='Original Data')

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_01[iso_flt].index, y=evi_sm_df_01[iso_flt].values, color='steelblue', label='Data after Isolation Forest Filtering')

<Axes: xlabel='time'>

The Isolation Forest result looks good. Not many points are classified as outliers, which I agree with from visual inspection. Better to be a bit conservative in this case and not remove too many points.

evi_sm_df_01_if = evi_sm_df_01[iso_flt]

Interpolation of missing values#

Remember that we initally had NaNs in the data? These were excluded when we created evi_sm_df_01 and subsequently applied the Isolation Forest filter. Let’s create a full series again with NaNs in the original positions:

evi_sm_df_flt = evi_sm_df.copy()

evi_sm_df_flt[:] = np.nan # Set all values to NaN

evi_sm_df_flt[evi_sm_df_01_if.index] = evi_sm_df_01_if.values # Fill in the filtered values

print("-- Original DataFrame --")

print("Total count:", len(evi_sm_df))

print("Nodata count:", evi_sm_df.isna().sum())

print(evi_sm_df.describe())

print("\n-- Filtered DataFrame (Simple threshold + Isolation Forest) --")

print("Total count:", len(evi_sm_df_flt))

print("Nodata count:", evi_sm_df_flt.isna().sum())

print(evi_sm_df_flt.describe())

-- Original DataFrame --

Total count: 523

Nodata count: 108

count 415.000000

mean 0.277122

std 0.720414

min -0.837399

25% 0.154266

50% 0.219401

75% 0.329128

max 14.230196

dtype: float64

-- Filtered DataFrame (Simple threshold + Isolation Forest) --

Total count: 523

Nodata count: 128

count 395.000000

mean 0.247526

std 0.111901

min 0.042567

25% 0.160532

50% 0.221382

75% 0.328961

max 0.563419

dtype: float64

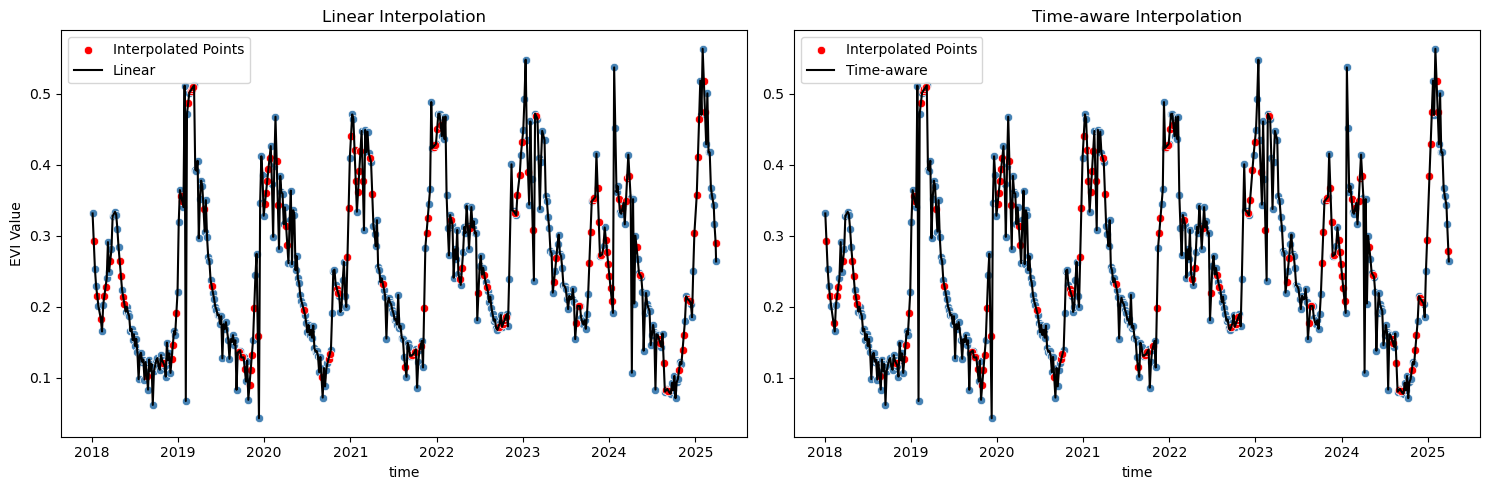

# Identify points that will be interpolated:

interpolated_pts = evi_sm_df_flt[evi_sm_df_flt.isna()].index

# Linear interpolation - connects points with straight lines

evi_sm_df_flt_intp1 = evi_sm_df_flt.interpolate(method='linear')

# Time-aware interpolation - accounts for actual temporal distances

evi_sm_df_flt_intp2 = evi_sm_df_flt.interpolate(method='time')

# Compare both methods

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(15, 5))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt.values, color='steelblue', ax=axes[0])

sns.scatterplot(x=interpolated_pts, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp1[interpolated_pts], color='red', ax=axes[0], label='Interpolated Points')

sns.lineplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt_intp1.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp1.values, color='black', ax=axes[0], label='Linear')

axes[0].set_title('Linear Interpolation')

axes[0].set_ylabel('EVI Value')

axes[0].legend()

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt.values, color='steelblue', ax=axes[1])

sns.scatterplot(x=interpolated_pts, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2[interpolated_pts], color='red', ax=axes[1], label='Interpolated Points')

sns.lineplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.values, color='black', ax=axes[1], label='Time-aware')

axes[1].set_title('Time-aware Interpolation')

axes[1].set_ylabel('')

axes[1].legend()

plt.tight_layout()

Well, both methods seem to result in similar outcomes here, but I’d go with the time-aware interpolation, as it considers the actual time intervals between observations, which is particularly important in time series data where observations may not be evenly spaced. Of course there are also other standard interpolation methods available in pandas (and other libraries), e.g., polynomial interpolation, spline interpolation, or more advanced methods. The choice of method depends on the specific characteristics of the data and the desired outcome. In this case, I think the time-aware interpolation is good enough and there is no reason to go for something more complex. Let’s proceed with fitting a smooth line to the filtered and interpolated data:

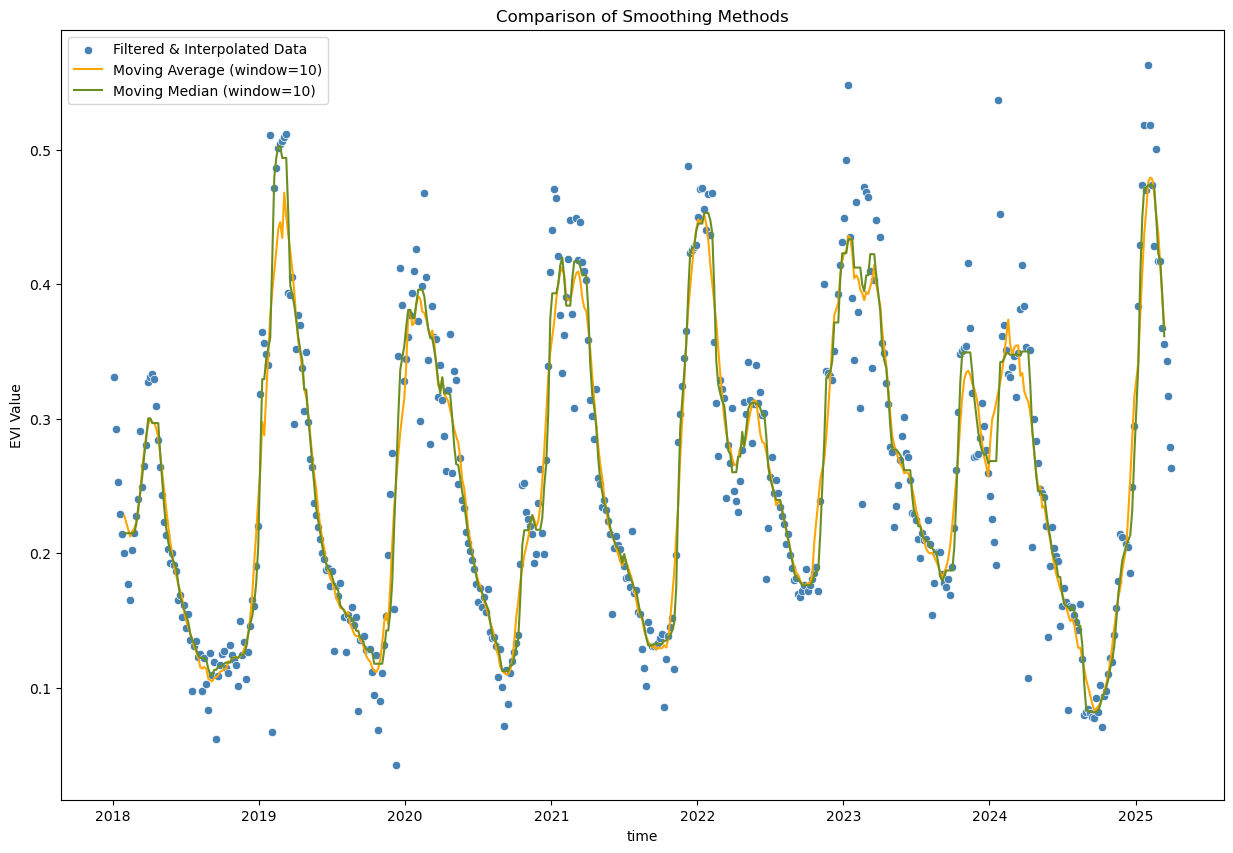

Fitting a smooth line to the time series data#

window_size = 10

# Moving average - simple smoothing

evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm1 = evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.rolling(window=window_size, center=True).mean()

# Moving median - alternative simple smoothing

evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm2 = evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.rolling(window=window_size, center=True).median()

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.values, color='steelblue', label='Filtered & Interpolated Data')

sns.lineplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm1.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm1.values, color='orange', label=f'Moving Average (window={window_size})')

sns.lineplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm2.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm2.values, color='olivedrab', label=f'Moving Median (window={window_size})')

plt.title('Comparison of Smoothing Methods')

plt.ylabel('EVI Value')

plt.legend()

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x7fd2f1fcd1f0>

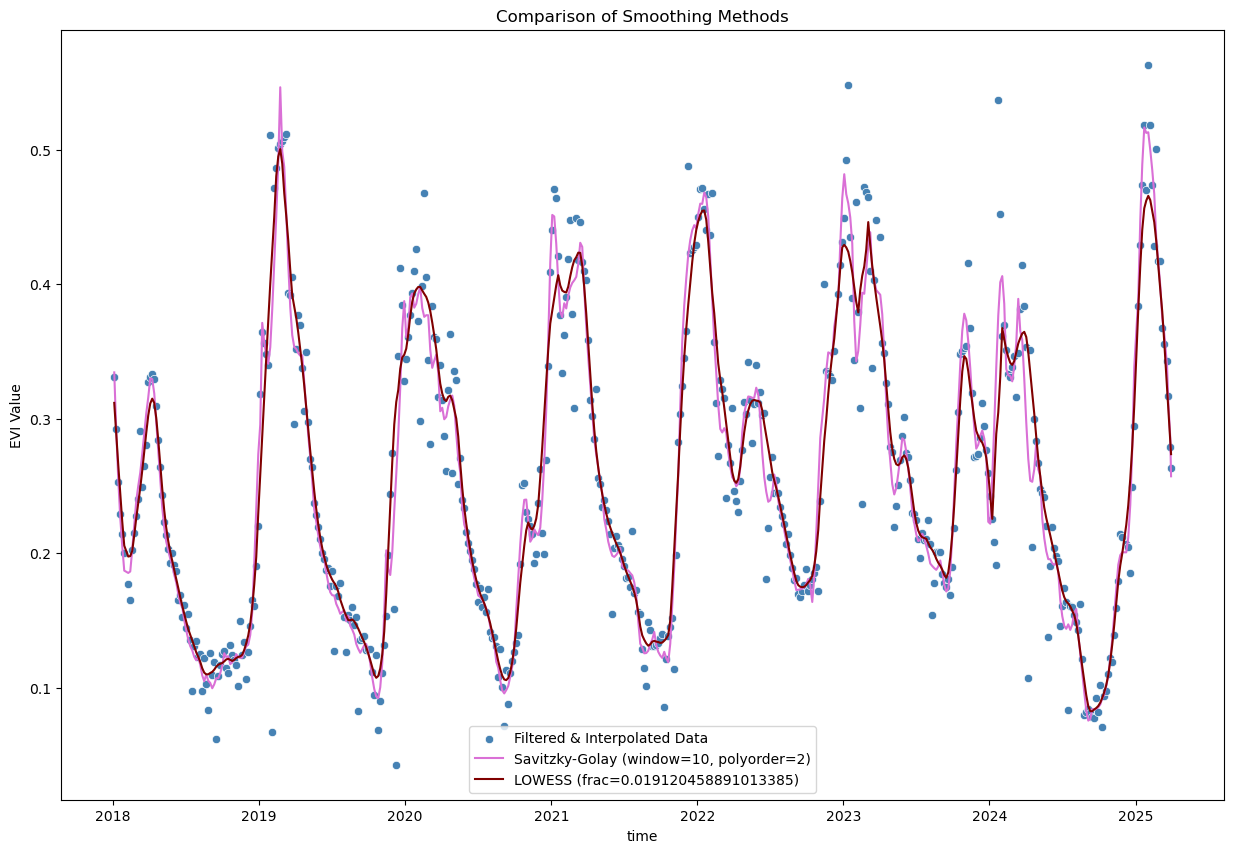

from scipy.signal import savgol_filter

from statsmodels.nonparametric.smoothers_lowess import lowess

# Savitzky-Golay filter

polyorder = 2

evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm3 = pd.Series(

savgol_filter(evi_sm_df_flt_intp2, window_length=window_size, polyorder=polyorder), index=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.index

)

# LOWESS smoothing

lowess_frac = window_size / len(evi_sm_df_flt_intp2) # fraction of data used for each local regression

evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm4 = pd.Series(

lowess(evi_sm_df_flt_intp2, evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.index, return_sorted=False, frac=lowess_frac), index=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.index

)

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 10))

sns.scatterplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2.values, color='steelblue', label='Filtered & Interpolated Data')

sns.lineplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm3.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm3.values, color='orchid', label=f'Savitzky-Golay (window={window_size}, polyorder={polyorder})')

sns.lineplot(x=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm4.index, y=evi_sm_df_flt_intp2_sm4.values, color='maroon', label=f'LOWESS (frac={lowess_frac})')

plt.title('Comparison of Smoothing Methods')

plt.ylabel('EVI Value')

plt.legend()

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x7fd2f1e7bfb0>

When to Use Which Method?#

Interpolation vs. Smoothing:

Interpolation: Use to fill gaps in your time series

Smoothing: Use to reduce noise in the overall signal (applied after interpolation)

Interpolation Method Selection:

Linear: Simple interpolation that connects points with straight lines

Fast and straightforward

Doesn’t account for irregular temporal spacing

Time-aware: Accounts for actual temporal distances between observations

More appropriate for irregular sampling (e.g. due to cloud masking)

Better preserves temporal dynamics

Gap limiting: Always use

limitparameter to avoid interpolating across large gapsRule of thumb: Don’t interpolate across more than 2-3 missing observations

Consider phenological cycles: don’t interpolate across seasonal transitions

Note: Polynomial and spline interpolation methods are also available in pandas (.interpolate(method='polynomial', order=2) or .interpolate(method='spline', order=3)), but can create unrealistic oscillations, especially near gaps or data boundaries.

Smoothing Method Selection:

Window size: Choose based on expected temporal dynamics of your variable

E.g., for vegetation indices with Sentinel-2 data (5-day revisit), a window of ~35-55 days (7-11 observations) is often appropriate

Moving Average: Simple arithmetic mean over a rolling window

Easy to understand and implement

Reduces amplitude of peaks

Good for initial exploration

Moving Median: Uses median instead of mean in rolling window

More robust to remaining outliers than moving average

Also easy to implement and understand

Better preservation of peak values than moving average

Slightly more computational cost

Savitzky-Golay: Fits local polynomials to smooth the data

Excellent for vegetation indices - very popular in remote sensing

Preserves peaks and trends better than moving average

LOWESS (Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing): Non-parametric regression method

Very flexible, adapts to local data structure

Good for complex seasonal patterns

fracparameter controls smoothness (smaller = less smooth)More computationally intensive

Can be sensitive to parameter choices

Important Considerations:

Always inspect visually - no single method is perfect for all cases

Window size matters - larger windows = smoother curves but may lose important details

Preserve seasonal dynamics - don’t over-smooth; you want to retain phenological patterns

Document your choices - make processing reproducible for your analysis

Consider your analysis goals: - e.g., trend analysis, phenology metrics, anomaly detection, etc.

Validate when possible - compare with visual inspection of original satellite images, ground truth data, or known phenological events